American Indian land comprises approximately 2% of the United States but contains an estimated 5% of the country’s renewable energy resources, according to a 2012 DOE Department of Indian Energy report, “Developing Clean Energy Projects on Tribal Lands.” Tribes can capture that potential in solar PV with the right combination of federal, state and tribal solar policy and funding opportunities.

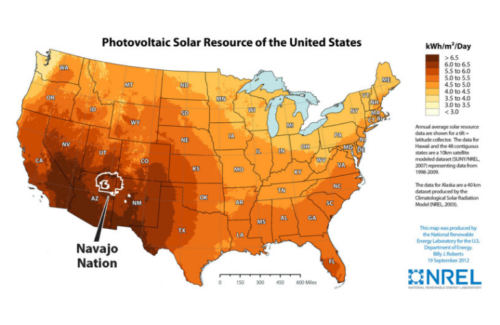

The Southwest United States specifically has some of the best solar resource in the country, and the Navajo Nation is right in the middle of it. According to NREL’s July 2018 report “Techno-Economic Renewable Energy Potential on Tribal Lands,” the Navajo tribal area has the highest technical potential for PV generation out of all tribes with 902,154 MW of capacity. The tribe is taking advantage of this resource — Navajo Nation President Jonathan Nez signed a proclamation in early 2019 to provide off-grid solar to the approximately 15,000 Navajo households still without electricity, according to Arizona Public Media.

In addition to deploying more PV on residences, the Navajo Nation is interested in developing more utility-scale solar like its 27.3-MW Kayenta Solar Facility that came online in 2017. The tribe is closing the Navajo Generating Station, a major coal plant, and going through a big energy shift.

“I think folks want to transition to renewables and get away from the fossil fuel industries because they’ve seen firsthand a lot of the after-effects with air and water quality standards going down,” said Tim Willink, member of the Navajo Nation and director of tribal programs at nonprofit solar installation and workforce development organization GRID Alternatives.

Volunteers from Fort Lewis College participate in GRID Alternatives solar installations for Solar Spring Break 2019.

GRID Alternatives is dedicated to advancing solar in the Navajo Nation and throughout Indian Country through its National Tribal Program, established in 2010. The goal of the program is to inform tribes on the possibility of solar and then assist with implementation, from educating on net metering and how to work with utilities to construction safety and installation practices. GRID recruits community members to volunteer to build grid-tied solar projects on homes and community buildings on tribal lands. In many cases, a tribe’s solar installation with GRID is its first.

“We really talk to them about their workforce development goals and we try and develop long-term partnerships so we can build upon and scale up these projects,” Willink said.

GRID trains construction workers within the existing tribal governments as well as interested community members, and also works with tribal colleges and high schools via its Solar Futures program. In the Navajo Nation specifically, GRID works at the grassroots level to recruit students from Fort Lewis College and Navajo Technical University to participate in Solar Spring Break and other training programs.

Policy is key for tribal solar

Solar installations on reservations are driven primarily by policy. There are some exceptions, like on the Spokane Reservation in Washington, where a few families have had the resources to install solar on their own. But in most cases, GRID partners with tribes on multiple levels to help make the policy changes necessary to grow solar on their reservations — engaging with the local government, central tribal government or tribal housing authorities.

Navajo Preparatory School students participate in a GRID Alternatives Solar Futures installation for the Lopez Family at the Ojo Encino chapter of the Navajo Nation in New Mexico.

GRID also works at the state level to make sure tribal interests are included in new solar legislation in progressive states like Washington, California and Oregon.

“Tribes are really trying to make sure that they have a seat at the table and that we’re not left out on this transition from fossil fuels to renewables,” Willink said. “If a state has a goal of 100% renewables, there should be a portion of that mandated for tribes to be involved in that conversation, in that movement, in that policy.”

In states that lack robust solar policies in general, tribes must find the resources and money to spearhead solar development themselves. That’s where GRID’s Tribal Solar Accelerator Fund (TSAF) comes in.

The fund came about after a few tribes asked GRID to go after some federal solar funding on their behalf, thinking it would be easier than the tribes applying individually. GRID agreed and succeeded, winning a $5 million, three-year grant from the Wells Fargo Foundation in 2018.

Navajo Technical University students participate in GRID Alternatives solar installations for Solar Spring Break 2019.

In the TSAF’s first year, GRID received 45 applications for $7.3 million worth of solar projects, according to Tanksi Clairmount, member of the Sicangu Lakota and Sisseton Wahpeton Dakota tribes and director of the fund. She said out of the 45 applications, 40 were very strong and could have received funding. But the organization only had $1.7 million to award for the year, which funded 14 different projects.

Tribes were excited for the federal grant opportunity because funding opportunities vary widely depending on what state they’re in. Even in states with solar programs, competition can be fierce.

“Tribes have to compete with state agencies and other large organizations for the same pot of funding,” Clairmount said.

The Department of Energy’s Office of Indian Energy Policy and Programs matches money from funds like TSAF to help increase funding for tribal solar projects. Tribes must come up with a 50% non-federal cost share to apply for matching funds through the DOE. If their projects are approved by the DOE, the tribes will be reimbursed by the federal government for the share they’re entitled to.

“We call our office a ‘do-with office,’ meaning we’ll do the work with you, we’ll partner with you to develop your capacity,” said Office of Indian Energy Director Kevin Frost. “The one thing we don’t do is we will not do the work for you, because that’s not what helps tribes overall when they’re self-determining their energy development and their future.”

Securing government funding for tribal solar projects has much to do with a tribe’s capacity — both politically and technically. The tribal council must spearhead the process and have resources in place to perform O&M and ensure the longevity of the system.

“Being good stewards of taxpayer dollars, we want to make sure that they can operate and maintain the equipment for the life of it, then that way it best benefits their tribal community,” Frost said.

GRID is there to help train tribes to make sure they are equipped to install, maintain and keep procuring solar on reservations.

“Indian Country wants to do this, tribes want to do this, the desire is there to increase our portfolio of renewables and develop our economies and to work toward energy sovereignty. And I think that if there’s more funding available on multi-levels, we could see a lot of progress in that realm,” Willink said.

A good and useful article! My wife and I have been interested in helping to fund off-grid solar for Nations like the Navajo Nation, and I think it is wise to empower the tribe to do the construction, O&M and also project planning for their projects receiving government assistance or GRID Alternatives, so that when it is time to repeat the project in a new part of the Nation, the skills are all there, it creates jobs, and the cost of the second through Nth projects are reduced. Thanks for giving info on this effort!

Reed Sims

Jericho, VT