Namaste Solar

Clean, local energy in the form of rooftop solar power is a powerful tool for fighting environmental injustice, but accessibility for the low-to-moderate income (LMI) community has been a stubborn barrier. Owning a home to put solar on in the first place is a challenge, and being able to afford a system is more complicated still. But a 2022 study by Lawrence Berkeley National Laboratory (LBNL) found some hopeful new trends in rooftop solar adoption.

Solar adopter incomes are declining over time, with the median solar adopter’s combined household income dropping from $129,000 in 2010 to $110,000 in 2021. Researchers found an average 1 to 2% drop per year over that period.

That’s still significantly higher than the U.S. median of $63,000 for all households and $79,000 for all owner-occupied houses, but it’s a notable shift.

“Once you average an entire country, it does look pretty gradual. And I think it gets a bit more interesting when you are able to play around with state- or county-level information,” said Sydney Forrester, scientific engineering associate in the electricity markets and policy department at LBNL.

At the state level, for example, an average of 55% of North Carolina’s solar adopters have an annual income below $100,000. But according to county-level data, 70% of solar adopters are making under $100,000 in a handful of North Carolina counties.

Researchers also found a substantial share of solar adopters that are considered LMI, with 22% of all 2021 adopters earning less than 80% of the area median income.

Part of the shift is attributed to rooftop solar broadening into LMI areas since 2016. The study found initial solar adopters in a county tend to be high-income, but as time goes on, the new adopters in the county start to reflect the area’s median income.

Researchers found that contractors with more than 1,000 systems installed are doing the most work with LMI households. Part of this trend is those installers are so large and widespread that they’re just capturing more of the LMI market. But these installers are also more likely to offer third-party ownership or solar leasing options for those who can’t afford the upfront cash or qualify for a big loan, increasing access to more populations.

“That, we think, is maybe because of just having more options. So, with more choices and more options, maybe there is an option that is just friendlier to low- and moderate-income adopters, even if they’re not necessarily targeting that demographic,” Forrester said.

The study also looked at race trends in solar adoption and found there’s been a national increase in Hispanic solar adopters and a decrease in white adopters. Since California makes up half of the country’s rooftop solar market, the large Hispanic population there is influencing these new stats. But this trend only holds true for English-speaking solar adopters. If the “primary householder” is Asian or Hispanic but doesn’t speak English as a first language, they are less likely to adopt solar.

This could be a result of solar companies not incorporating different languages in advertising, or the lack of education and awareness of state and federal tax incentives that help make solar more affordable.

“It shows the compounding effect of language in addition to ethnicity, which impacts the adoption equity,” Forrester said.

White and Asian households are still generally over-represented among solar adopters, while Hispanic and Black households are under-represented relative to the general population in each state. At the aggregate national level, solar adopters in 2021 were 12% Asian, 7% Black, 25% Hispanic and 55% white.

“Black households are more universally, no matter how you cut it, underrepresented. [But] there’s diversity among states. There are some states that are doing better than others,” Forrester said.

There’s still work to do to make rooftop solar access a reality for less-affluent households and increase racial equity in deployment, but progress is starting one percentage point at a time.

This story is part of SPW’s 2023 Trends in Solar. Read all of this year’s trends here.

“Solar adopter incomes are declining over time, with the median solar adopter’s combined household income dropping from $129,000 in 2010 to $110,000 in 2021. Researchers found an average 1 to 2% drop per year over that period.”

There’s the statistics, then there’s the actual experience in adopting the technology for one’s own use. Back in 2005 the Wife and I had solar PV put on the roof of our home, our combined buying power was well under the $129,000 or the $110,000 statistics quoted in the article. During that 2010 to say 2020 period interest rates were low, State, Utility and Federal (ITC) subsidies were in place and the price of installing solar PV on one’s roof changed from the 2005 rate of right at $8.30/watt installed to today at something like $3/watt installed without subsidies and around $2/watt installed with subsidies. That puts the cost availability to households that make a combined $60,000 a year, without subsidies and around $42,000 with subsidies. It seems for 2023 one can carry the ITC over to a second year to offset the Federal taxes for two consecutive years, allowing more capture of the ITC for low income families.

Things the wife and I learned from the install of the solar PV array on our home’s roof in 2005. Yes it was quite expensive, the “simple ROI” calculated out to 22 years for payback in electricity savings. The (Things) the energy industry won’t tell you is, back in the day (2005) the cost of electricity was right at $0.11/kWh, today it is right at $0.17/kWh as bundled retail rate costs are added to the wholesale value of electricity. When one hit $0.12/kWh, often the ROI was right around 15 years payoff. Right now in California with block tiered electricity rates, TOU rate spiking, folks are finding out if they put in a large solar PV array, smart ESS and buy into a new or used BEV, they can save something like $6,000 to $10,000 a year in combined energy costs and pay for their solar PV + ESS in 5 years or less.

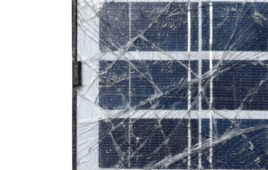

There are still some actually claiming, the solar PV won’t pay off, because, you’ll have to replace panels every 10 years. (IF) the panels aren’t damaged by natural events, there are solar PV panels like Maxeon on the market now that have a linear 40 year power production warranty. Solar PV panels degrade in the sun and become worthless. Another lie told by corporate energy and swallowed by the retail electricity public hook, line and sinker. The new crop of manufactured solar PV cells and panels have a LID of 2% the first year of use and from a high of 0.7% to a low of 0.25% a year thereafter. SO, today a solar PV panel of 400 watts operating undamaged for those 40 years would lose 2% efficiency the first year and 0.25% every year after for 39 years and have a power output of right around 353 watts after 40 years of use. The price of solar PV panels (today) one could add around 25% more panels and have a robust 40 year solar PV array. Roughly $4K to $6K more in panels to make a more reliable energy generation array for the next 40 years. The old grid tied solar PV array we had on the house since 2005, did indeed degrade over years of use. The find here is every time someone replaces an old appliance in their home with a new Energy Star appliance, you need less energy to run your household and still have enough generation each day to offset your average daily energy needs. THIS is a marathon, not a sprint. I haven’t experienced electricity rates going down in the last 30 to 40 years and it seems like the overall trend is electricity per kWh is NOT going down anytime soon, unless you pay it forward and get your own electricity generation system.